Digital Feature: The reality of FuelEU in numbers

R. BAX, Lloyd's Register, London, England, UK

FuelEU represents a major market intervention by the European Union (EU), pushing shipping companies to increase their uptake of renewable and low-carbon fuels by setting requirements on the greenhouse gas (GHG) intensity of all fuels.

Today, many owners and managers are concerned with the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), designed to reduce emissions produced by shipping. However, the author's company's projections show that the impact of FuelEU will eclipse that of the ETS around 2035 and dwarf it beyond that. Business as usual is therefore no longer an option, and progressive decisions must be made to deal with this challenge.

The FuelEU regulation systematically promotes more sustainable fuels, but significant penalties loom for those shipping companies that do not make the transition. Ships of at least 5,000 GT must reduce the GHG intensity of their fuels by 80% against a 2020 benchmark to 2050 or face penalties. This change will be stepped with initial small targets, increasing as 2050 approaches, as does the level of intervention needed to comply.

How each organization adapts to FuelEU is a complex challenge because of the numerous options – from the costs of doing nothing, to making interventions that can drive competitiveness – that are available to shipping companies.

A hierarchy of fuel. The EU takes a view on each of the different fuels available to shipping companies, resulting in a hierarchy. At the top, carrying the greatest benefits are renewable fuels of a non-biological origin (RFNBO), produced by combining green hydrogen with other elements such as carbon or nitrogen extracted from the atmosphere. At the bottom, fossil fuels carry the greatest penalties. Somewhere in between are biofuels, produced from biological sources.

The costs of doing nothing. Without any interventions, ships running the same heavy fuel oil/marine gasoil (HFO/MGO) mix as today will be subject to penalties, and an annual multiplier

Penalties for a fleet of five ships, each using 5,000 metric tons/yr (tpy) of fuel, between 2030 and 2034 without intervention (well-to-wake intensity is 91.40 gCO2eq/MJ) is shown below:

Making a compliant fleet. This hypothetical fleet of five ships could take several routes to become compliant. This analysis considers two credible routes to 2034: the first considers increasing proportions of biodiesel; the second is a similar fleet but with increasing proportions of bioLNG in a single DF LNG ship.

These biofuels have been chosen not because these are ‘better’ fuels – they will not be appropriate or even relevant for many fleets. However, as drop-in fuels, both are relatable because they are available now and use existing ship infrastructure.

As other parts of the EU’s Fit For 55 package of regulations kick in, more alternative fuels will become available, presenting strategies that will be more appropriate for a wider range of fleets.

Beyond 2035, the total cost of operations becomes less clear as they rely on a multitude of emerging factors, including the supply of RFNBOs and how these fuels will be priced by the EU.

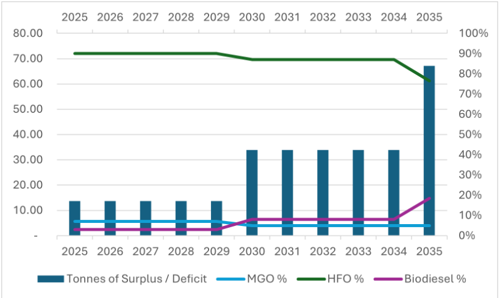

SCENARIO 1: BIODIESEL

This scenario shows how a single ship using 5,000 tpy of HFO-equivalent fuel can maintain FuelEU compliance by steadily raising the proportion of biodiesel in its fuel mix in five year increments: to 3% from 2025, to 8% from 2030 and then to 19% from 2035. This scenario does produce a small compliance surplus, measured in the tens of tons per year.

In this small fleet of five ships, every ship would need to adopt this strategy for the whole fleet to be compliant.

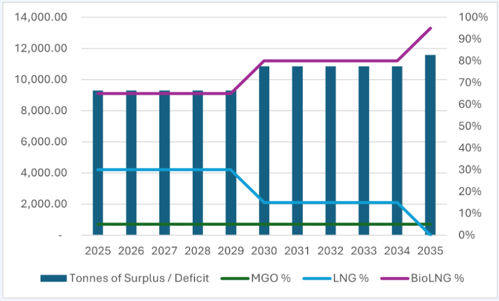

SCENARIO 2: BIOLNG

This scenario shows how the pooling element of FuelEU can work within a fleet.

In the same example of five ships, four run as usual on a 90% HFO/10% MGO mix. The fifth vessel runs on a mixture of LNG and bioLNG, with the proportion of bioLNG rising to 95% by 2035.

While both the biodiesel and bioLNG examples both comply with FuelEU, the regulation’s pooling mechanisms mean that in this example, one bioLNG ship’s surplus covers the deficits for the other four ships in the fleet, making the whole fleet compliant up to 2034 as the proportion of bioLNG rises.

The bioLNG ship has a surplus compliance of 9,287 tons in 2025, rising to 11,576 tons in 2035, compared to just 67 tons for the biodiesel example. By increasing the proportion of biodiesel in the previous example, greater surpluses could be achieved.

In this example, the surplus compliance is so large initially that this one ship covers the compliance deficit of 17 similar ships annually between 2025 and 2029 – this surplus could be bought by third parties or potentially a secondary market at some point in the future.

This surplus reduces to five ships between 2030 and 2034 as FuelEU tightens and then covers just itself in 2035. Further interventions would then be necessary to make those remaining ships compliant.

From 2035, one option could be to transition to eLNG, an RFNBO, which is expected to have a lower GHG intensity than bioLNG, but as the figures for eLNG are not yet set in the second phase of the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive and this fuel is not yet produced in any meaningful quantity, accurate projections are difficult to make.

But these examples demonstrate a basic principle: FuelEU incentivizes those who are over-compliant by creating a new market within which to sell surplus compliance. While every intervention incurs a cost, it can also generate a return.

And returns can be significant. If a ton of CO2 equivalent emissions could be worth at least €500 on the open market, and you can save 7,500 tpy of CO2 equivalent emissions, you see how this can quickly turn into a significant driver of revenue. More drastic interventions could generate more impressive returns.

Additional benefits. There are further benefits to compliance. New directives in the EU and U.S. mandate companies to manage their Scope-3 (indirect) emissions – those produced by its value chain, which will inevitably include shipping.

Those shipping companies waiting to see what to do will not only be subject to penalties and the need to buy surplus compliance, but could also see reduced income as their customers switch to lower carbon competitors.

The economics invert away from fossil fuels towards lower carbon. In this respect, FuelEU cannot be considered just as an imposition, but a major market intervention within which shipping companies with vessels operating in European waters must operate to build a profitable and sustainable future.

Comments